in silico NAMs and AI's Role In the Future Without Animal Testing

Illustration created with OpenAI. It represents in silico approaches in drug development. Credit: Belma Alispahić.

Article written by Belma Alispahić.

This article is Part 2 of a blog series exploring technologies that are changing how drug safety is assessed. Part 1 focused on biological alternatives such as organoids and organ on a chip systems. This piece turns to the digital layer that increasingly connects and scales those models.

In November 2025, the UK government published a roadmap aimed at accelerating the reduction of animal testing for medicines. Earlier the same year, the US FDA released its own plan to expand the use of non animal approaches in drug development. These announcements did not come out of nowhere. They formalized a shift that has been underway for years.

Yet the question that often follows is the wrong one.

The debate is usually framed around whether animal testing can be replaced. That framing assumes a clean swap, one method exchanged for another. In reality, what is changing is not a single experiment, but how evidence is generated, combined, and trusted across the development pipeline.

Much of that change sits within what are known as in-silico new approach methodologies, or in-silico NAMs.

In silico NAMs: A Digital Layer, Not a Replacement

In drug development, in-silico NAMs are a family of computational approaches that use artificial intelligence, mathematical modeling, and biological knowledge to estimate how drugs behave in the human body.

They are not experiments in isolation, but decision-making tools.

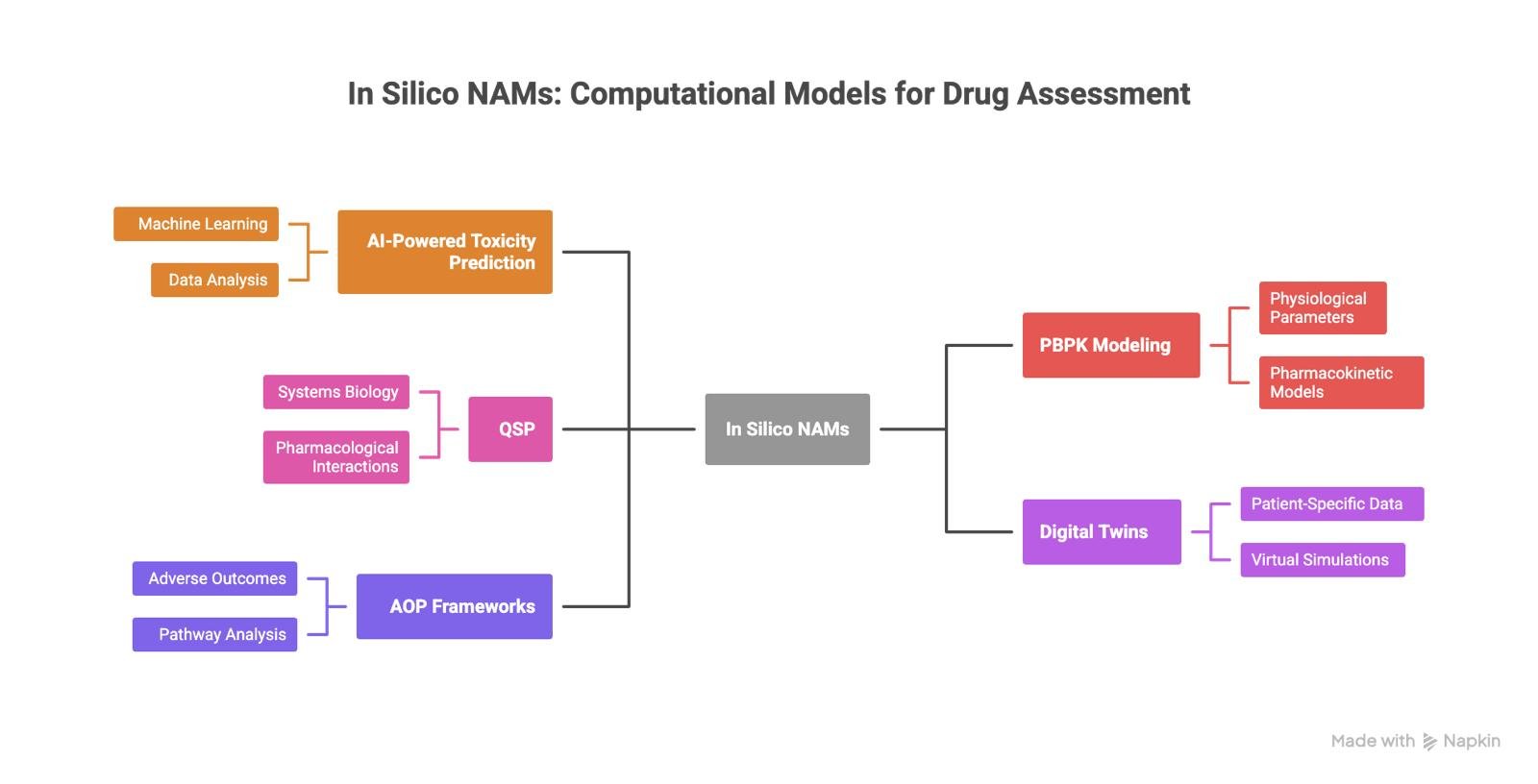

In practice, in-silico NAMs include AI-based toxicity prediction, physiologically-based pharmacokinetic modeling, quantitative systems pharmacology, digital twins and virtual patients, and adverse outcome pathway frameworks. Each addresses a different question, at a different scale, and with different levels of uncertainty.

What they share is timing. These methods move critical assessments earlier, when decisions are still flexible and failure is cheaper.

Schematics showing the different in silico NAMs. Image created using Napkin AI by Belma Alispahić.

Predicting toxicity with AI before synthesis

One of the most persistent causes of drug failure is toxicity that appears too late in the testing journey. Despite decades of animal testing, a substantial part of development failures are still linked to unexpected safety issues.

AI based toxicology models address this problem upstream. By evaluating chemical structure and existing biological data, they estimate risk before a compound is synthesized or tested. The value is not speed alone, but speed combined with selectivity. Fewer weak or risky candidates move forward.

There is no single AI model for toxicity. Different endpoints behave differently. Cardiotoxicity linked to hERG channel blockade benefits from deep learning and graph based models that preserve molecular structure. Hepatotoxicity often relies more heavily on physicochemical features and known structure toxicity relationships. Neurotoxicity remains difficult, but hybrid approaches combining multiple data representations are improving early signal detection.

The gains are specific, not universal. AI designed or filtered compounds show higher success rates in early phase safety studies, and human cell based in-silico cardiac models can outperform animal tests in predicting arrhythmia risk. This does not eliminate uncertainty. It changes where uncertainty is confronted.

PBPK and QSP: making exposure and biology explicit

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling, or PBPK, is one of the most established in silico approaches in regulatory science. These models describe how a compound moves through the human body by representing organs, tissues, and biological processes explicitly.

PBPK models are already used to inform dosing, drug drug interactions, and population specific effects, often reducing the need for certain clinical or animal studies. The models’ strength lies in transparency. Assumptions are visible. Parameters can be challenged. Predictions can be stress tested.

Quantitative systems pharmacology, or QSP, extends this idea to disease and drug mechanism. QSP models describe how drugs interact with biological systems over time, often using differential equations to represent complex feedback and pathway interactions.

Together, PBPK and QSP do not aim to predict outcomes in isolation. They aim to make reasoning explicit. They help teams ask whether observed effects are plausible, under which conditions they break down, and where additional evidence is needed.

Digital twins and virtual patients

One of the most interesting in silico NAMs are patients’ digital twins. At a larger scale, digital twins and virtual patients attempt to simulate variability.

Virtual patients are computational representations generated from population level data. They allow researchers to explore how differences in physiology, genetics, age, or comorbidities affect response without exposing real individuals to experimental risk.

Digital twins go a step further by emphasizing correspondence with real world counterparts, often integrating longitudinal data to update predictions over time.

These approaches enable virtual clinical trials, scenario testing, and sensitivity analysis. Their value is not prediction alone, but comparison. They make it possible to explore “what if” questions systematically and identify where uncertainty concentrates.

Adverse outcome pathways and trust

One of the central concerns around in-silico methods is trust. Predictions without explanation are difficult to defend, especially in regulated contexts.

Adverse outcome pathways, or AOPs, address this gap. An AOP describes how a molecular initiating event triggers a sequence of biological changes that lead to an adverse outcome. It is a mechanistic map, not a statistical shortcut.

Quantitative AOPs link early events to downstream effects, allowing exposure thresholds and species specific differences to be explored explicitly. They provide the biological context that allows in silico predictions to be interrogated rather than accepted at face value.

This matters because regulatory acceptance does not hinge on novelty. It hinges on traceability.

What Can in-silico NAMs Do for Drug Development?

Over 90 percent of drug candidates fail during clinical development, largely due to poor translation of safety, exposure, and efficacy from preclinical models to humans. In-silico NAMs address this problem by using human relevant data earlier and more deliberately.

Regulators are not removing standards. They are redefining evidence. The trajectory points toward animal studies becoming the exception rather than the default, supported by combinations of in-vitro and in-silico methods.

Organoids and organ on a chip systems generate biologically rich data. In-silico NAMs scale, contextualize, and test that data across scenarios that physical experiments cannot cover alone. Together, they offer something animal testing struggles to provide consistently: mechanistic insight at human scale.

The Real Challenge Ahead

The main barriers are no longer conceptual. They are operational.

Data quality, model validation, interpretability, and integration into existing regulatory workflows remain open challenges. Validation takes time. Trust is cumulative. Adoption will be uneven.

But the direction is clear. The question is no longer whether in-silico NAMs belong in drug development. It is where they create the most value today, and how they are combined responsibly with other methods.

The shift away from animal testing will not be sudden. It will be structured, layered, and evidence driven. In-silico NAMs are not the end of that process. They are the connective tissue that makes it possible.

About the author:

Belma Alispahić is a scientist and technology entrepreneur working at the intersection of life sciences and artificial intelligence. Her work focuses on computer based models and digital simulations that help scientists better understand complex biological systems and improve how drugs are developed. With experience across research and industry, she connects scientific insight with real world decision making. Belma writes and speaks about innovation, impact, and the future of technology in the life sciences.