Organoids and Organ-on-a-Chip: The Technologies Replacing Animal Testing

On 11 November 2025, the UK government announced plans to phase out animal testing for drugs. This follows the US FDA's decision from earlier this year to reduce animal testing requirements for monoclonal antibodies and other therapies.

These regulatory shifts are more than policy changes. They represent recognition that two technologies, organoids and organ-on-a-chip systems, have matured enough to serve as viable alternatives to animal models in drug development.

Global Context of Animal Testing

Some animals used for research go through noninvasive tests, given harmless injections, placebo, or mild medications. This is not the case for all. Moreover, the definition of “animal” is contested here. In the US, mice are not recorded as animals for research, so numbers of mice used are hard to estimate. Additionally, most studies refer to mammals when they talk about animals, but millions of flies (Drosophila melanogaster) and nematodes (Caenorhabditis elegans) are used but not counted in the data as “animals”.

UK animal use

The UK government's announcement positions the country alongside the US in prioritizing human-relevant testing methods. The decision follows decades of commitment to the 3Rs principle (replacement, reduction, refinement), which recommends that scientists avoid animal testing when alternatives exist. In 2023, the UK used 2.68 million animals in scientific studies.

EU and USA animal use

The European Union conducted 9.3 million animal experiments in 2022, with an additional 9.6 million animals bred but not used in experiments. Europe is also pushing to reduce animal experiments for testing chemical safety.

In the US, data on the number of mice used for research, the most used mammal for research, are not counted, so it’s hard to know. Some organizations estimate that 50 million animals are likely used for studies in the US. The FDA's 2025 roadmap encourages developers to leverage AI-based computational modeling, human organoids, and organ-on-a-chip systems to predict drug behaviour and toxicity.

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs): Alternative technologies to animal testing.

There are alternative to animal testing that have been developed for decades, and these are now providing satisfactory results. This is the reason behind organizations moving away from animal studies for drug discovery and testing. These alternatives are collectively known as “new approach methodologies”, or NAMs.

So what are new approach methodologies (NAMs)? These encompass a set of physical and digital tools and techniques to assess safety and efficacy of drugs and chemicals, none of which involve more than cells.

NAMs are divided in two main categories: “in vitro” (literally "in glass") methods using living cells outside organisms, and “in silico”, methods using computational models. This article focuses on in vitro models and approaches, specifically organoids and organ-on-a-chip systems, which are the most prominent and useful in-vitro assays to replace animals in drug testing. A follow-up piece will address in silico alternatives including AI, machine learning, and digital twins.

Organoids: Miniature Organs From Stem Cells

Organoids are three-dimensional, self-organizing structures derived from stem cells that mimic the cellular composition and architecture of real organs. This makes them powerful tools for drug and chemical testing.

Cell cultures have been used for decades to test the efficacy of drugs. But most cell cultures only have one type of cell, and they grow in layers or suspension. This means that they do not resemble real organs or tissue, which is three-dimensional. Organoids are still in-vitro models but developed in 3D scaffolds, which allows cells to interact more naturally and form tissue-like structures.

Researchers typically generate organoids from embryonic stem cells, adult stem cells, or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (skin or blood cells from patients that are reprogrammed to become stem cells). The stem cells self-organise into organ-specific structures, exhibiting near-physiological cellular composition and behavior. Importantly, organoids do not have only one type of cell. For example, brain organoids contain neurons, astrocytes, and supporting cells. Liver organoids develop hepatocytes and bile ducts. Intestinal organoids form villus-like projections mimicking the gut lining.

The main advantage of organoids stems from their human origin. One in four new medicines fails because of brain side effects that didn't appear in animal testing, and 95% of drugs intended to treat brain diseases fail in clinical trials. Brain organoids made from human stem cells can show what will actually happen in human patients more accurately than animal brains. And organoids can be made from the cells of a single patient, giving rise to more personalized approaches focused on the physiology of a single individual.

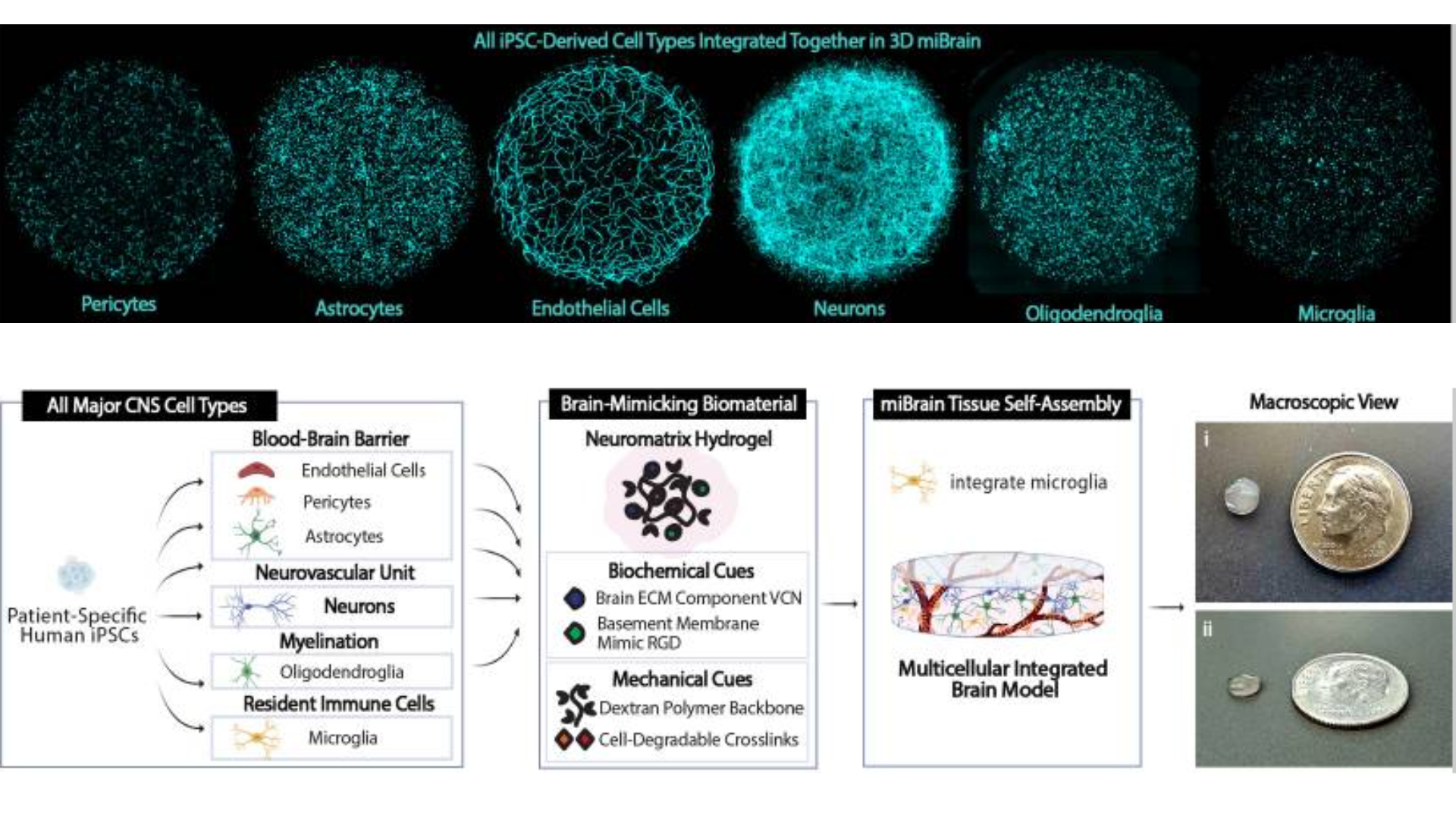

A great example is the miBrain model, developed at MIT, which integrates all six major brain cell types (neurons, astrocytes, microglia, oligodendroglia, pericytes, and brain microvascular endothelial cells) in a 3D hydrogel scaffold. The system shows blood-brain barrier function, neuronal connectivity, and myelination.

So why have we not adopted organoids for everything? Organoids have drawbacks too. They are not that easy to produce, and they are not like a full brain, just rather small replicas, missing detail, size, and the rest of a human body, with its myriad complexities. This means that, while you can do a lot more than in normal cell cultures, the data from organoids studies does not correlate fully to human studies.

The miBrain model. Source: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12557797/

Organ-on-a-Chip: Engineered Microenvironments

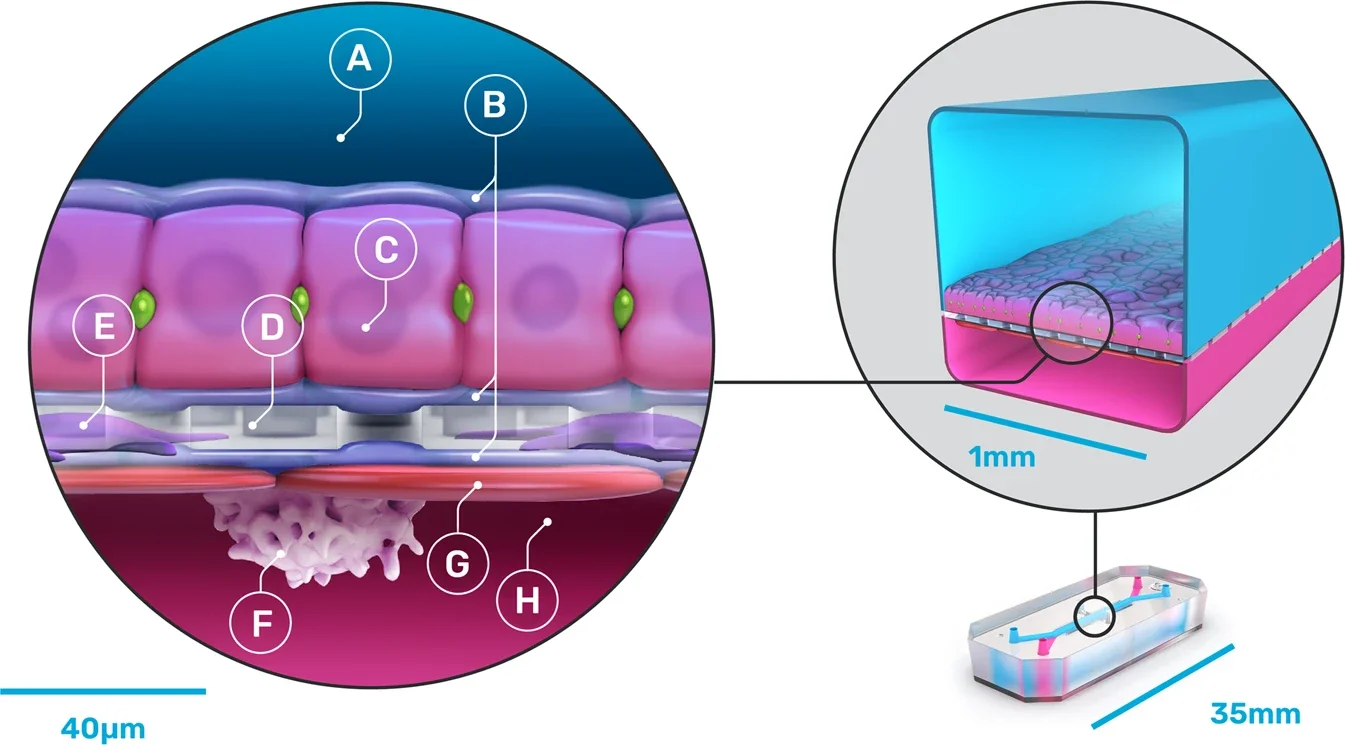

Organ-on-a-chip (OOC) systems are microfluidic devices lined with living human cells cultured under fluid flow to replicate organ-level physiology. To make them. tiny channels and wells are carved into small chips the size of a couple of your fingers. Nutrients flow through the channels and cells grow in the wells. This mimics circulation and real environments and forces that your cells suffer too. Drugs or chemicals can be added to the fluid in the microfluidic channels, making these in vitro models ideal for drug discovery.

A kidney-on-a-chip, for example, can have proximal tubule cells exposed to fluid flow rates matching those in human kidneys. A lung-on-a-chip recreates the lung's air-liquid interface with mechanical breathing motions. This way, researchers can create dynamic environments with fluid flow, mechanical stretch, and biochemical gradients, to study how cells to behave in living organs rather than in static culture dishes.

Predictive accuracy data supports OOC utility, and there are multiple examples. One study demonstrated 89% accuracy of in silico drug trials using human cardiomyocyte models in predicting clinical arrhythmia, versus 75% accuracy using animal models. A proximal tubular OOC successfully predicted the nephrotoxicity of SPC-5001, a drug that showed kidney damage in Phase 1 human trials but not in preclinical testing on mice and non-human primates.

Schematic of a liver format of organ-on-a-chip. Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43856-022-00209-1

What the Transition Looks Like

Pharmaceutical companies aren't waiting for mandates. Big Pharma is building AI infrastructure and acquiring proven molecules while licensing organoid and organ-chip tools from specialized providers. Contract research organizations (CROs) like Dynamic42 and Cherry Biotech are selling OOC platforms to pharma companies, allowing drug developers to outsource alternative testing without building internal capacity.

Academic institutions are validating new models and training the next generation of scientists in these methods. Startups focused on specific organ systems (brain, liver, kidney) are attracting venture capital and forming partnerships with established pharma. The FDA's pilot program allows select monoclonal antibody developers to use primarily non-animal-based testing strategies under close FDA consultation, generating data that will inform broader policy changes.

Organoids and organ-on-a-chip market evaluation

The business opportunity is substantial. Companies providing organoid and organ-chip technologies, along with AI-driven analysis platforms, are positioned to capture market share as regulatory pressure for change intensifies.

In the case of organoids, the market in 2025 is valued at $1.4 billion, but projections say it will reach $4.0 billion by 2035, registering a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.7% over 10 years.

For organs-on-a-chip, the growth is much larger. In 2024, the organ-on-a-chip market was worth of $157.3 million, but projections put it at $952.4 million by 2030. This means a CAGR of 35.11% for oragan-on-a-chip technologies.

What This Means for Animals and Humans Worldwide

Globally, with an estimated 192 million animals used in scientific research (and I see this as a very conservative estimate), the potential reduction is huge.

If organoids and organ-chips can replace even a fraction of these experiments, they can save millions of lives. For pharmaceutical research specifically (about 9% of animal procedures in the UK), NAMs could eliminate hundreds of thousands of animal experiments annually in the UK alone.

Beyond animal welfare, the shift addresses a scientific problem. Species differences between animals and humans lead to misleading results, with drugs that work in animals failing in human clinical trials at rates of over 92%. Organoids and organ-on-a-chip don't just save animals, they improve drug development by using human cells that respond the way human patients will.

Note: A part 2 featuring in-silico NAMs like digital twins, AI, ML, will be published soon.